In America, where “having it your way” is a major selling point for everything from fast food to home-building, and making your own way in the world is the gold standard of achievement, individualism stands as the ideal for realizing the American dream. But when and why did this concept take hold in the American imagination, and how does it continue to influence our society and political system today—for better or worse?

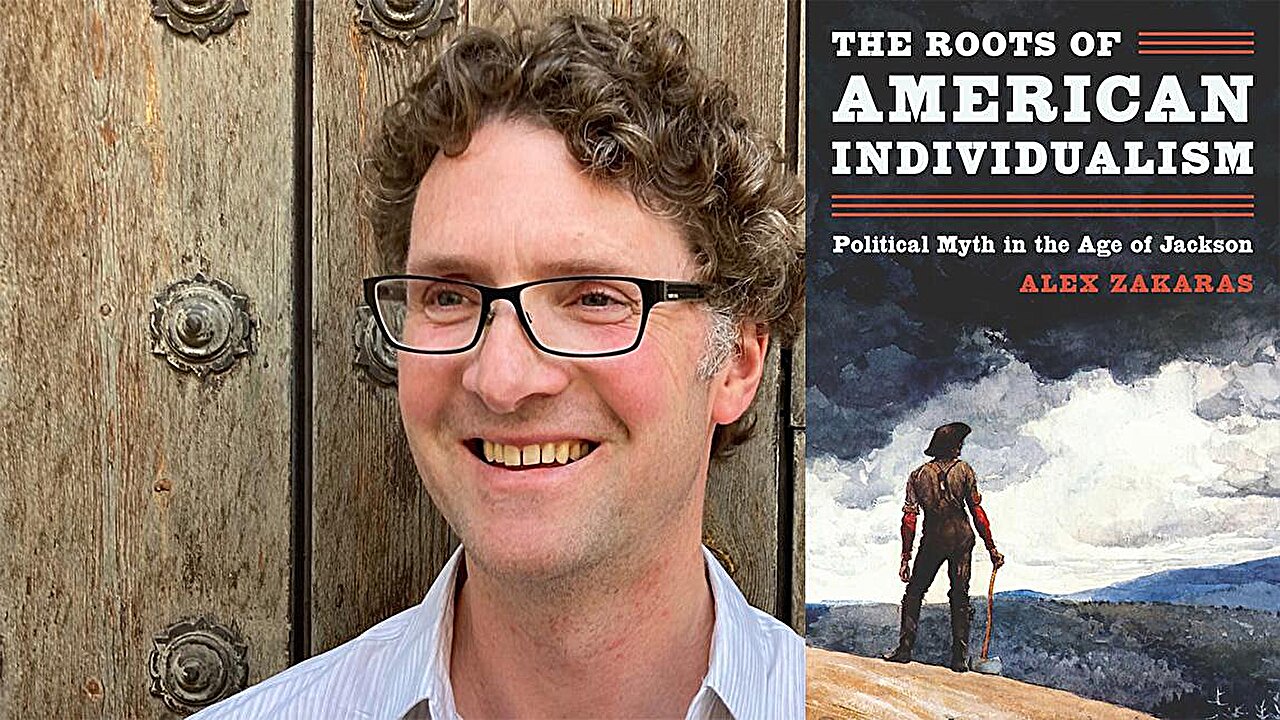

A spirit of independence has embodied the American mystique since the country’s beginnings, but during the Jacksonian era, the American way of thinking about politics and society grew significantly more individualistic. In a new book, “The Roots of American Individualism: Political Myth in the Age of Jackson,” Alex Zakaras, Ph.D., professor in the UVM Department of Political Science, argues this point, tracing the establishment of this ideal back to an often unsung time in the country’s history, and illustrates how it continues to pervade our society and political system to this day.

Recently named Best Book in American Political Thought for 2022 by the American Political Science Association, the book primarily focuses on Jacksonian America, roughly from 1820 to 1850. It is organized around three key myths—the myth of the rights-bearer, the myth of the independent proprietor, and the myth of the self-made man—and explores how these ideas were used in political argument and helped shape American political thinking.

Delving into newspaper articles, campaign speeches and pamphlets, sermons, Fourth of July orations, and more, Zakaras shows how the language of American politics underwent significant changes during this period, with long-term implications. “These myths, this discourse that was so prominent in the Jacksonian era, are still quite powerful today,” Zakaras says.

The myth of the rights-bearer, one of the origin stories about America centered around the earliest settlers who were fleeing religious and political persecution, persists in our modern conversations around the second amendment and gun rights, for example. If the current dialogue were framed around public health and safety as opposed to personal freedom, Zakaras says, we would think more about balancing such different interests as parents’ concern for their kids’ safety and the desire to own firearms for hunting and self-defense.

But, he adds, “rights language tends to entrench us in absolute claims, so that any incremental encroachment seems like an assault on one’s autonomy.” This kind of absolutism doesn’t leave a lot of room for middle ground or compromise in modern America when it comes to such issues as speech rights, abortion rights, or COVID policies, which are often seen as invasions of individual rights and freedoms.

The myth of the independent proprietor was the story that emphasized the property-owning small farmer, epitomizing American freedom. With land came status and standing in the community and control over the foundation of your own economic life. The belief was that not having to depend on others was what enabled you to stand your ground and speak your mind as a free citizen.

“I think we can see resonances with this, for example, in the modern discourse around welfare in our society,” says Zakaras, “the idea that depending on outside help is somehow humiliating and demeaning, that it reduces you to something less than a civic equal.” Even in the Jacksonian Era, he adds, “this was partly disingenuous, because there was a great deal of political interest in having government supply cheap (or free) land to white settlers who were moving West.”

The third myth, that of the self-made man, has also persisted since Jacksonian times. When Americans are asked in polls whether success or failure is more a matter of individual control or forces outside one’s control, they are more likely to say the power lies with the individual.

Zakaras argues that this meritocratic perspective, which sets Americans apart from Europeans, has harsh political consequences: It leads affluent people to believe that they deserve everything they have and that any effort to create a more egalitarian society is unfair because it rewards the undeserving. “I think we have a harder time than many other affluent democracies in adopting common-sense policies designed to promote the public good, policies that demand some measure of shared sacrifice,” he says.

A major theme in the book is the relationship between individualism and race, particularly in terms of white supremacy. “The languages of personal freedom were continually used to reinforce racial hierarchy during the Jacksonian period, and that’s been another important legacy,” Zakaras says. “The hero of these three myths was almost always a white man, and most white men at the time believed that their own personal freedom included the right to dominate and control others—including women and people of color.” They tended to see the pursuit of racial and gender equality as an attack on their God-given entitlement to do as they pleased.

Another important theme in the book is utopianism. In the 19th century, Americans tended to believe that the old world was corrupt and defined by authority, and that the new world represented a new start for humanity unleashed from repressive aristocratic constraints. This story of living in a classless society free from arbitrary limitations has remained part of our society for more than two centuries.

“But the more you’re attached to this story, that individuals can be whoever they want to be and go wherever they want to go,” Zakaras says, “the more challenging it is for you to consider any alternative way of thinking about America.” One of the reasons so many Americans are viscerally resistant to the lessons of critical race theory, Zakaras suggests, is that it bluntly challenges this mythologized vision of the nation and its history.

Zakaras notes that he is not out to condemn American individualism outright. He says that the language of personal freedom is quite adaptable, and that “we need to lay claim to it in ways that would press toward a more socially equal society.” In the book, he cites how the Abolitionists in the Jacksonian era were able to do just that. “They used the languages of personal liberty and expansive individual rights to press for not just the end of slavery and anti-discrimination measures in the North, but also a pretty broad vision of what it would mean to be free.” He adds that the languages of personal independence also were used throughout much of the 19th century to criticize rising economic inequality.

We don’t have to abandon the language of individualism altogether, Zakaras stresses, even if we’re frustrated by the ways in which freedom is used in our current discourse—in fact, we shouldn’t. Individualism runs deep in the American psyche, and those who are able to harness it gain an important political advantage. “It’s not about rejecting individualism altogether; it’s about understanding its complexity and the ways in which we can make use of it more productively,” he says. With this book, Zakaras has provided an excellent first step on the path toward doing just that.

Provided by

University of Vermont

Citation:

The myths and truths of individualism in America (2023, December 13)

retrieved 13 December 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-12-myths-truths-individualism-america.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.