Likening it to providing more runways at busy airports, researchers at North Carolina State University found in a new study that adding protruding rocks to restored streams can help attract female aquatic insects that lay their eggs on the rock bottoms or sides.

More eggs that hatch into larval insects is great news for stream restoration because the re-establishment of organisms, such as insects, is often slower than expected in restored streams, says Brad Taylor, associate professor of applied ecology at NC State and corresponding author of a paper describing the research.

A thriving population of stream insects generally portends good water quality and overall stream health and provides food for fish, amphibians, reptiles, and even birds, he adds.

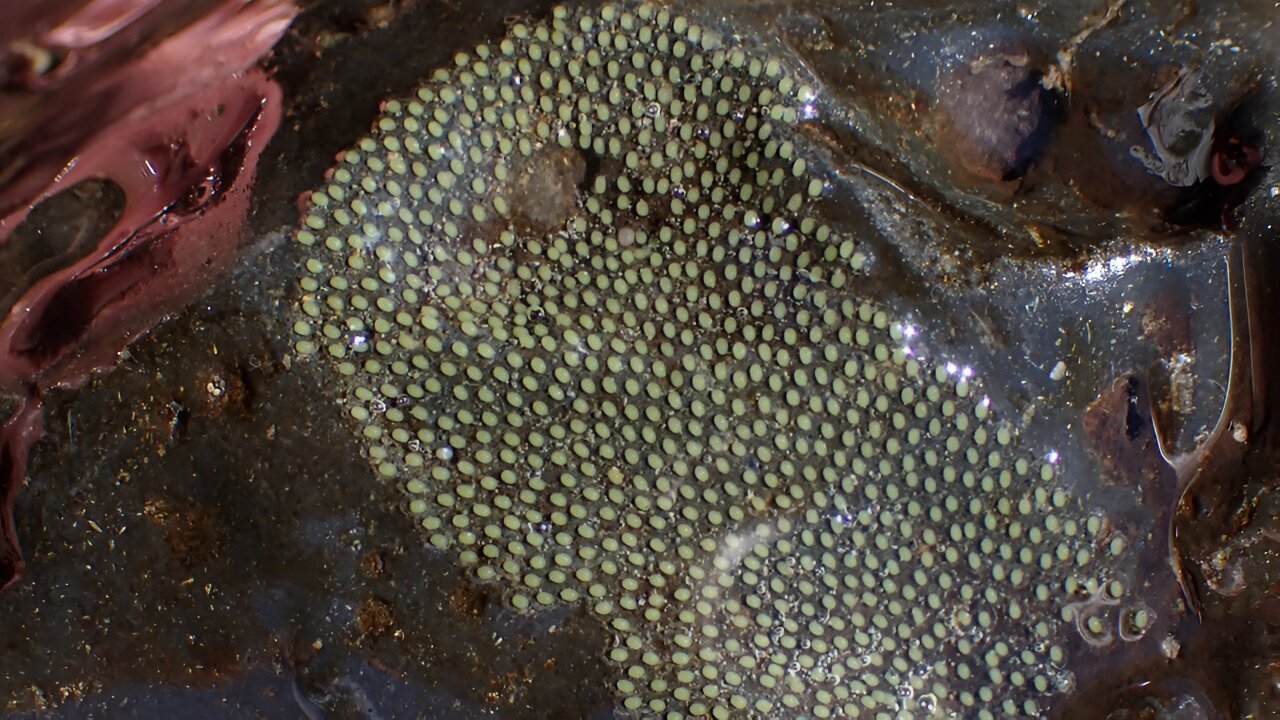

Most stream insects use rocks protruding above the water as runways to land on, then crawl underwater and attach their eggs to the underside of the rocks. Because restored streams sometimes fail to regain their abundance of aquatic insects even decades following restoration, researchers were interested in testing whether increasing egg-laying habitat in the rock landing areas would increase the abundance and diversity of insect eggs and larvae.

Taylor and NC State graduate student Samantha Dilworth selected ten restored streams in northwestern North Carolina and added protruding rocks gathered near the streams to five of them; the other five restored streams did not receive additional rocks.

The results showed that the streams with added protruding rocks had almost twice as many egg masses compared to the untreated streams. After adding rocks, egg numbers in treated streams were similar to those in undisturbed streams downstream of state parks and national forests.

“This study was a successful proof of concept: adding rocks to restored streams enhances the abundance and diversity of stream insect eggs,” Taylor said.

The researchers also discovered that some rocks were more attractive to females and received most of the eggs; many rocks received few or no eggs.

“The insects are really putting all their eggs in one basket, so to speak, or onto a few rocks,” Taylor says. “A future goal is to figure out how and why females select specific rocks so that any rocks added to streams get used because moving large rocks around a stream is hard work.”

The study also showed that the response of the larval stages of stream insects was weaker than expected based on the increase in eggs in restored streams.

“We can restore aquatic insect eggs by adding rocks, but we didn’t see a consistent increase of the larval insect stages,” Taylor said. “The second year of the study was one of the wettest in recent years, so a lot of the rocks rolled. Insects in restored streams with no added rocks also declined, while those with added rocks did not change or increase, but not as much as expected.”

“We observed that many rocks rolled, which could have caused eggs to be crushed or exposed to air where they would dry out and die. These sources of egg mortality may explain the weaker increase of larval insects, as some eggs may have never hatched into larvae.”

“Also, higher larval mortality in restored streams could have been caused by factors unrelated to disturbance of the rock egg-laying runways. For example, priority or primacy effects by established insects or other organisms could be excluding newly arriving insects, and food resources could be limiting larval insects, or other disturbances of larval habitats could be occurring.”

Taylor plans to follow up with research on how best to stabilize protruding rocks using hydrologic modeling to determine the best locations. To extend the runway metaphor, what will make rocks more like O’Hare International Airport runways than a local grass or gravel airstrip?

“If we can get this information to restoration practitioners, they can add rocks that are both more attractive to female insects and stable,” Taylor said. “This will make restoration efforts more cost-efficient and effective. There are miles of restored streams, so there are lots of rocks needed. We want to make sure every rock gets eggs.”

The study appears in Ecological Applications.

More information:

Samantha Dilworth et al, Facilitating the recovery of insect communities in restored streams by increasing oviposition habitat, Ecological Applications (2023). DOI: 10.1002/eap.2939

Provided by

North Carolina State University

Citation:

Aquatic insects in restored streams need more rocks to lay their eggs (2023, December 13)

retrieved 13 December 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2023-12-aquatic-insects-streams-lay-eggs.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.